The SCO's Tianjin summit and the South Caucasus: signals for a shifting order

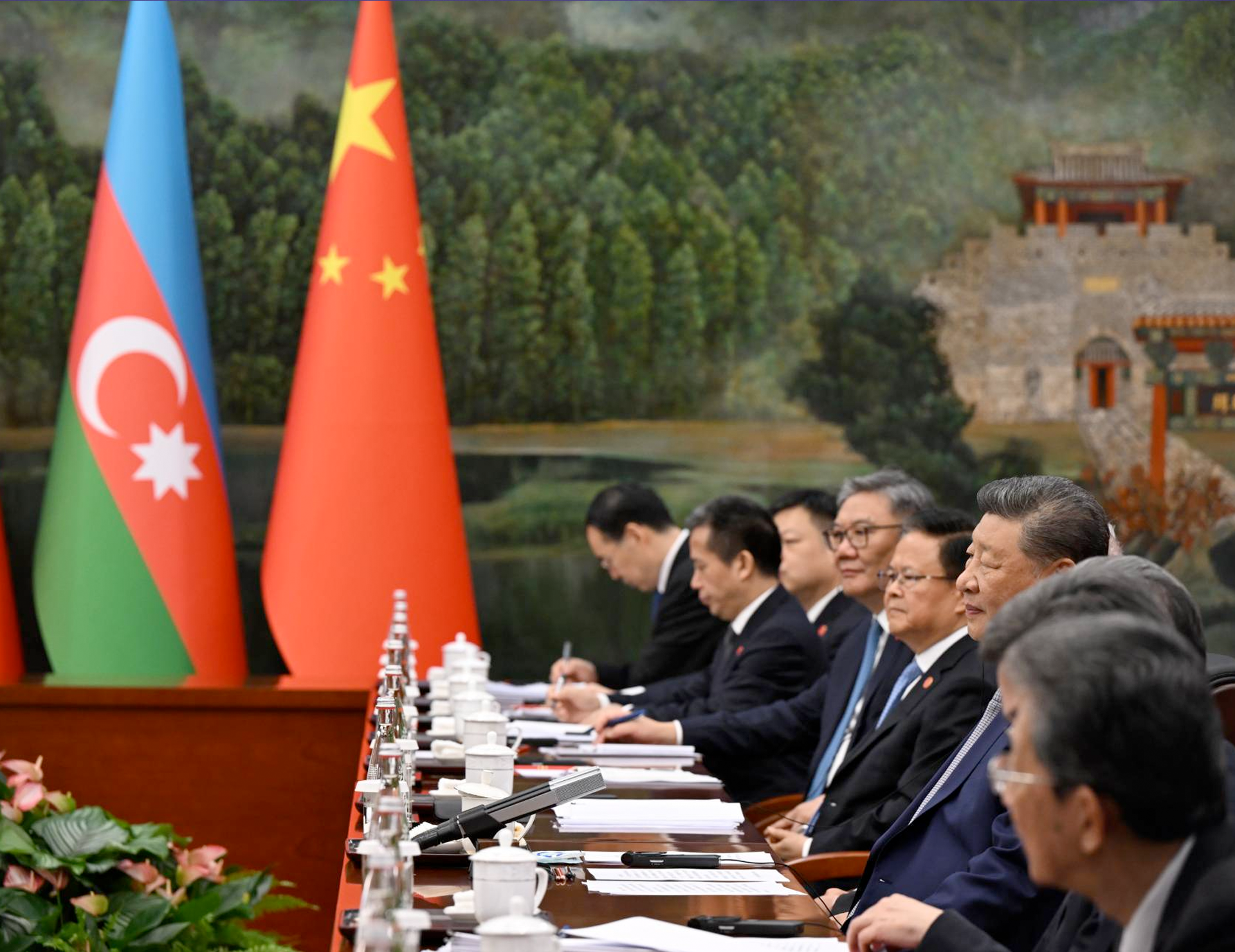

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) gathered for its latest summit in Tianjin at the turn of August and September, bringing together leaders from across Eurasia under the watchful eye of China. Established in 2001 as a forum primarily for security cooperation, the SCO has grown into a heavyweight in global governance. Today, its members represent around 40 percent of the world’s population and roughly a quarter of global GDP, making it one of the largest platforms outside of the Western-led system. The summit highlighted Beijing’s ambition to expand the group’s role not only in security but also in economic and technological cooperation, with President Xi Jinping unveiling plans for an SCO development bank, new initiatives in artificial intelligence, and expanded financial assistance. Against this backdrop, the South Caucasus states found themselves in the spotlight, each in different ways.

For Armenia, the summit was particularly rewarding. On July 3, Yerevan officially announced its intention to join the SCO, on the basis of its alignment with the organization’s principles of territorial integrity, non-use of force, and inviolability of borders.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan used his trip to China to deepen ties with Beijing, with the two countries formally elevating their relations to the level of a strategic partnership. This step comes at a time when Armenia is seeking new avenues of support in its foreign policy, and the SCO provides a framework in which it can position itself as an active Eurasian player.

An additional breakthrough was the decision by Pakistan, a member of the SCO, to recognize Armenia’s independence, ending decades of diplomatic non-recognition rooted in Islamabad’s close partnership with Azerbaijan. For Yerevan, these developments amount to a diplomatic windfall, offering new channels of cooperation and recognition at the very moment it seeks to diversify its foreign relations.

Azerbaijan also used the occasion to strengthen its profile within the organization, albeit in a more pragmatic fashion. President Ilham Aliyev’s meetings in Tianjin were focused on deepening economic cooperation, particularly with Chinese companies and financial institutions. Among those he met were representatives of China National Chemical Engineering Corporation, PowerChina Group, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and China Electronics Technology Group Corporation. Talks also extended to China Communications Construction Company, a firm blacklisted by the United States.

For Beijing, Azerbaijan is increasingly indispensable. The Middle Corridor, which links China to Europe via Central Asia and the South Caucasus, has been gaining momentum. In 2024 alone, 287 freight trains crossed from China into Azerbaijan, carrying some 378,000 tons of goods, which represents an 86 percent increase compared to the previous year. This surge proves Baku’s growing role as a transit hub and explains China’s keen interest in anchoring long-term cooperation with Azerbaijan. The SCO summit thus served as a useful platform for Aliyev to reinforce Azerbaijan’s credentials as a fundamental partner in Eurasian connectivity.

The margins of the summit also provided opportunities for delicate diplomacy. Pashinyan and Aliyev met face-to-face to continue discussions on the Armenia–Azerbaijan peace agenda, while the Armenian leader also held talks with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Both meetings were framed as steps toward stability in the South Caucasus, though the road remains long and fraught with obstacles.

President Aliyev’s lack of a private meeting with Vladimir Putin was telling. Despite both leaders’ presence in Tianjin, their absence of direct talks highlights the ongoing tensions in Azerbaijani-Russian relations, which have increasingly grown over the past year.

By contrast, Georgia was absent altogether. Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze dismissed the need to attend, noting that Georgia is not a member of the SCO. Yet the decision was widely read as another sign of Tbilisi’s self-isolation at a time when regional integration initiatives are proliferating around it. As Armenia and Azerbaijan move closer to the SCO and deepen their dialogue with China, Georgia risks being sidelined from an emerging Eurasian framework that could shape connectivity and diplomacy in the years ahead.

China’s framing of the SCO as an alternative to Western-led frameworks, combined with the South Caucasus countries’ growing interest in joining Beijing-led institutions, underscores how the region is evolving from a shared EU-Russian frontier into an important node of rivalry between a fragmented West and an ambitious China.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Eastern Partnership states – and particularly those in the South Caucasus – were pressed to choose between EU Association Agreements and membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. That zero-sum dilemma has since faded, as these countries increasingly look to China to diversify their strategic options.

Having an FTA with Beijing in place since 2017, Georgia signed a strategic partnership agreement with China in July 2023. Azerbaijan followed suit in 2024 and went a little further by upgrading its ties with China to the level of a comprehensive strategic partnership in April 2025. At the SCO summit in Tianjin, Armenia signed a strategic partnership agreement with China.

Closer engagement with Beijing and its multilateral platforms offers South Caucasus countries valuable geopolitical leverage, enabling them to tap into fresh markets while avoiding costly ruptures with established ones. Unlike the EAEU, partnership with or membership in the SCO or BRICS does not place regional states in the opposing camp to their Western partners, at least for now. At the same time, joining such organizations offers Azerbaijan a subtle means of soft balancing, helping it offset the political and security pressures emanating from Moscow, Tehran, and New Delhi. Through multilateral venues like the SCO, Baku can dilute bilateral asymmetries by embedding its interactions with these countries in a broader institutional framework, thereby reducing the scope for direct pressures.

In the security realm, South Caucasus states may increasingly embrace what some other small and middle powers have adopted elsewhere: security hybridization. This would involve cooperation with the United States to bolster external deterrence, coupled with engagement with the SCO to manage internal security threats, including the so-called 'three evils' cited in SCO documents.

In August, during President Aliyev’s visit to the Oval Office, President Trump extended the long-standing waiver of Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act, effectively reopening the door for U.S. defense assistance to Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, Baku sees in the SCO an opportunity to anchor its position on territorial integrity and resistance to separatism within a broader multilateral framework, even though these principles had not always enjoyed uniform support among SCO members.

For countries like Azerbaijan, wary of compromising their strategic autonomy, the SCO’s relatively modest commitments create a permissive framework, one that allows them to draw on the bloc’s economic and political mechanisms without ceding sovereign control. It also sits well with these countries’ increasingly multivectoral foreign policy, bolstering eastern vector of their geopolitical posturing amid the global power shift from the west to the east.

One concern for South Caucasus states, however, is the prospect of Russia breaking out of isolation, an outcome that could allow Moscow to consolidate its position in Ukraine and redirect attention to other regions of vital interest, including the South Caucasus. Within the span of two weeks, President Vladimir Putin met with Donald Trump and Xi Jinping, the leaders of the world’s two superpowers, reaching a series of formal and informal understandings that could strengthen Russia’s hand in shaping the emerging rules of the international order.

Trump has on different occasions signaled his openness to a Yalta-style arrangement that would divide spheres of influence with Moscow, effectively acknowledging Russia’s primacy in the post-Soviet space. China, for its part, seeks Russian backing to counterbalance Western dominance in global affairs and to advance a vision of orderly multipolarity that respects Moscow’s claims over its near abroad.

In Tianjin, Russia and China signed a memorandum on building the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, which will deliver up to 50 billion cubic meters of gas per year from Russia’s Arctic gas fields of Yamal to northern China via Mongolia. Although details on pricing, take-or-pay terms, financing, or delivery schedules remain unresolved, the memorandum nonetheless signals a geopolitical shift: Moscow is redirecting Yamal gas flows from Europe to China, while Beijing, abandoning its calculated ambiguity, signals a readiness to defy the Western sanctions regime. China has also started to receive liquefied natural gas from Russia’s sanctioned Arctic LNG 2 plant. Yet the Russia–China gas pact was not the only signal of Moscow’s declining future role in Europe’s gas markets. On September 5, at an informal EU energy ministers’ meeting in Copenhagen, Energy Commissioner Dan Jørgensen declared that, even if peace is achieved in Ukraine, the EU must never again import a single molecule of Russian energy. For Azerbaijan, this shift underscores an opportunity: Europe’s accelerated break with Russian gas is likely to raise demand for alternative suppliers, making the Southern Gas Corridor an increasingly important component of EU energy security.

Meanwhile, even if China is careful to respect Russia’s interests in the post-Soviet space, Moscow may find it increasingly difficult to rely on its traditional strategy of 'managed instability' in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, a policy line that risks undermining China-backed projects.

With the Middle Corridor thrust into the spotlight after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China has begun to take a more active role in investing in the corridor’s physical infrastructure as well as its regulatory and logistical frameworks. In May 2024, Georgia announced that a Chinese consortium would construct Anaklia deep-sea port, the largest one in the Black Sea, highlighting Tbilisi's growing ties with Beijing. In November 2024, China, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan signed an agreement to build an intermodal cargo terminal at the Alat Port in Baku, which will increase container train traffic along the China-Europe-China route via the Middle Corridor. Interestingly, China’s growing footprint in the South Caucasus offers regional countries a balancing mechanism to leverage in their dealings with Russia.

In the end, the SCO’s Tianjin summit underscored a widening geopolitical truth: for Armenia, Azerbaijan, and even an absent Georgia, engagement with Beijing offers opportunities for diversification and leverage, but also new dependencies that must be carefully managed. Moscow’s lingering influence, coupled with Beijing’s expanding footprint, creates both risks of entanglement and prospects for balancing. What is clear is that the South Caucasus cannot insulate itself from the structural shifts of Eurasian geopolitics. Instead, its states are learning to navigate them by adopting flexible, multivector strategies. How successfully they do so will determine whether the region emerges as a mere arena of great-power rivalry or as an active participant in shaping the new regional order.