The end of the JCPOA era? Multilateral diplomacy meets military escalation

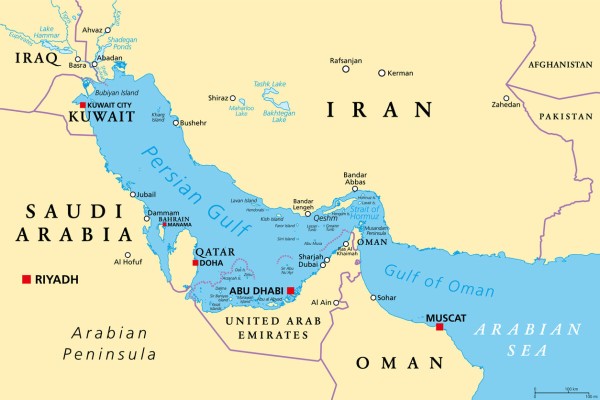

Following the ceasefire that ended the twelve-day Iran-Israel war, tensions surrounding Iran’s nuclear program are approaching a pivotal juncture: the imminent expiration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015. Many of the mechanisms embedded in the resolution, including the critical snapback mechanism, will cease to apply after 18 October 2025, unless the agreement is renewed or replaced by a new framework. In a significant development, on 12 June, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)’s 35-member Board of Governors formally concluded that Iran is in violation of its obligations under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). This marks the first such formal finding in nearly two decades and raises the likelihood of the issue being referred to the United Nations Security Council. In the immediate aftermath of this resolution, Israel initiated a comprehensive aerial offensive targeting Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, military and dual-use assets, nuclear scientists, and senior commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). On 22 June, the United States entered the conflict in support of Israel, launching precision strikes with B2 bombers and Tomahawk missiles on Iran’s key nuclear sites in Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan.

Currently, according to Axios, diplomatic efforts are underway to resume nuclear negotiations. White House special envoy Steve Witkoff and Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi are expected to meet in Oslo. A high-ranking Iranian political source explained to Amwaj.media that “deep mistrust and a fundamental lack of confidence” have constituted core impediments to restarting negotiations in the wake of U.S. and Israeli airstrikes on Iran, including those targeting nuclear installations. This evolving diplomatic landscape cannot be fully understood without close attention to the legal and procedural mechanisms embedded within the JCPOA framework, particularly the so-called “snapback” provision, which functions as both a deterrent and an enforcement tool. As the expiration date of the agreement nears, the fate and potential reactivation of this mechanism have returned to the center of international debate.

Unless Tehran and Washington reach a new agreement, the snapback mechanism may be invoked to reinstate UN sanctions on Iran. The snapback mechanism is considered one of the most strategically crafted tools of the JCPOA and diplomatic history. It is a process that allows for the quick reimposition of previously lifted UN sanctions on Iran, as outlined in UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA). The snapback mechanism is triggered when a current JCPOA participant, such as France, the UK, Germany, China, or Russia, submits a complaint claiming that Iran has seriously failed to meet its commitments under the agreement. After this complaint is submitted, the Council’s president is required to propose a resolution within ten days that would allow sanctions relief to continue by dismissing the complaint if no other member of the UN Security Council has already done so. However, if the Security Council does not pass such a resolution within 30 days, all previously lifted UN sanctions are automatically reinstated. The advantage of this process is that it cannot be blocked by a Security Council permanent member’s veto. If a country like China or Russia vetoes a resolution to maintain sanctions relief, the result is the opposite: the sanctions are restored once the 30-day period ends.

Given that the JCPOA is expected to be extended in October and that it seems unlikely Russia and China will take action under the current circumstances, Europe's role in applying diplomatic pressure on Iran is becoming increasingly important. The United States unilaterally withdrew from the deal under the Trump administration in 2018, with Trump calling the agreement “one of the worst” in American history. Two years later, in August 2020, the U.S. attempted to invoke the snapback mechanism. In response, the British, French, and German governments issued a joint statement asserting that the U.S. “was no longer a participant and therefore lacked standing to invoke the snapback mechanism under UNSCR 2231.” They instead opted for an EU-led diplomatic approach to preserve the JCPOA.

But the configurations of parties have shifted today. While the U.S. has taken a tunnel-vision approach, the E3 have assumed a hawkish posture by advocating for the imposition of draconian restrictions on Iran. While increasing the tensions with Netanyahu over Gaza and pre-French mandates Syria and Lebanon, Macron calls for increased pressure on Iran. Israel, which has traditionally dismissed diplomatic tools when it comes to Iran, has now called on the E3 to activate the snapback mechanism.

Europe’s desire to assume a leading role in reimposing sanctions is driven by a number of interconnected motivations. One of the most important factors among them is the undeniable role of Iranian drones in Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. According to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Iran may have supplied Russia with around 3,000 drones, mostly Shahed-136s. One of the provisions suspended by the JCPOA was an embargo on all conventional arms transfers to and from Iran. The EU is now factoring the potential reinstatement of that embargo into its strategic calculations on the Ukraine war. Even if snapback sanctions are not reimposed, leveraging the threat of their return could present an opportunity to induce a rupture in Iran–Russia relations.

Although Iran has supplied Russia with over 3,000 Shahed-136 drones and hundreds of long-range missiles, Moscow has refused to provide even Su-35 fighter jets to Tehran, while offering its more advanced Su-57 aircraft to India. This asymmetry in defense cooperation could lead to growing tensions in the Iran–Russia relationship. If the EU prioritizes this issue in future negotiations, the Iranian might be forced to reconsider its military and trade alignment with Moscow to safeguard its political survival.

Another motivation behind the EU's potential willingness to invoke the snapback mechanism lies in its need to restore cohesion in Transatlantic relations, which were strained during Trump’s second term. That glue for strained relations could be built geographically through Syria, with Turkey’s cooperation, or through Iran with Israel’s. After Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018, the U.S. lost its political leverage to use the snapback mechanism. Although the U.S. has continued to impose unilateral sanctions on Iran, the EU responded by developing countermeasures such as the “Blocking Statute”. As a result, the U.S. now depends on the political tools that the E3 still possesses to mount a comprehensive sanctions regime against Iran. The EU is well aware of the value of this leverage and is likely to use it as a bargaining chip in its dealings with Washington.

In parallel, Tehran may interpret such renewed pressure as a justification for recalibrating its nuclear posture. Iranian officials have clearly stated that reimposing UN sanctions would trigger a strong response from Tehran, and it may withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) if the snapback mechanism is used. After Pezeshkian’s order to suspend Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA, questions arose about its potential intent to withdraw from the NPT. However, Iranian Foreign Minister Aragchi stated that “Iran remains committed to the NPT and its Safeguards Agreement,” and called reports of a full suspension “fake news.” He also added that collaboration with the IAEA “will be channeled through Iran’s Supreme National Security Council for obvious safety and security reasons.” This institutional change suggests that inspections will become more restricted, politically controlled, and securitized. Following the securitization priority of Tehran, all diplomatic engagement related to nuclear oversight seems to be funneled through a security-focused institution instead of technocrats and scientific experts.

Although Iran’s foreign minister reaffirmed the country’s commitment to the NPT, Tehran may still consider withdrawing from the treaty in response to the damage it perceives from the Israeli-American attack and as a way to assert its national sovereignty. Such a move could be justified by claiming that its national interests have been violated. Iran’s threshold proliferation strategy—standing on the brink of nuclear weapons capability as a warning of “build the bomb if pressured”—has effectively collapsed. At the same time, Iran’s security doctrine of “exporting conflicts beyond its borders” has also unraveled, largely due to the severe damage suffered by the Axis of Resistance proxies after October 7, 2023. Tehran now feels compelled to develop a new deterrence tool capable of preventing direct attacks by the U.S., Israel, or other political actors. One such option gaining traction is moving beyond merely “being on the threshold” to actually acquiring nuclear weapons. This approach is especially championed by hardliners within the regime. The approximately 900 casualties in Iran from Israeli strikes, coupled with the public’s anger now consolidating around hostility toward Israel and the U.S., and a rising nationalist sentiment, all indicate that the hawkish faction holds a stronger hand compared to moderates.

The IAEA believes that Iran managed to obtain at least 400 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent purity before the air strikes. Highly enriched uranium at 60 percent purity is enough for use in a nuclear weapon. The common claim that Iran requires “weapons-grade” uranium enriched to 90 percent or more to develop a nuclear explosive is wrong. Iran has a strong chance of keeping its highly enriched uranium both secure and hidden. This material is stored in small cylinders about the size of scuba tanks, making them extremely hard to track. Also, Iran likely still possesses the equipment needed to enrich this uranium further. It is unclear if Israel has destroyed Iran’s centrifuge production facilities, but Tehran maintains a significant stockpile of centrifuge parts. After the U.S. withdrawal in 2018 from the JCPOA, the IAEA has lost its ability to effectively monitor these components. Iran’s getting a nuclear bomb will be a politicized policy instead of a technical one.

The United States is currently confronted with a strategic dilemma: should it risk a second Iraq-style debacle by taking coercive measures to prevent Iran’s nuclear proliferation, or should it tolerate Tehran’s uranium enrichment and centrifuge stockpiling at the expense of potentially facing a second North Korea scenario? Both options are fundamentally misaligned with the prevailing orientations of U.S. Middle East policy, whether pursued by the Pentagon/Establishment faction or under the Trump administration’s more unilateralist approach. To avert the emergence of a nuclear-armed Iran, Washington may employ calibrated diplomatic pressure, sustain engagement channels, and adopt a sophisticated carrot-and-stick strategy aimed at empowering Iran’s moderate factions within the regime. Creative interim arrangements and flexible bargaining frameworks may offer a path toward de-escalation and strategic deterrence.

In this increasingly fragmented strategic landscape, the survival of the nuclear non-proliferation regime depends not only on technical compliance but also on political foresight and institutional restraint. As the JCPOA approaches expiration, the choices made by Iran, P5+1, and Israel will define not just the trajectory of Iran’s nuclear program but the credibility of NPT itself. If the snapback mechanism is activated without a viable diplomatic off-ramp, it may mark the point of no return for Iran’s nuclear ambiguity and possibly for the NPT. Conversely, if Europe succeeds in leveraging the threat of sanctions to reopen meaningful negotiations, it could reaffirm the utility of coercive diplomacy while averting a broader regional conflagration. The coming weeks may very well determine whether the JCPOA’s final chapter becomes a case study in collapse or in recovery.